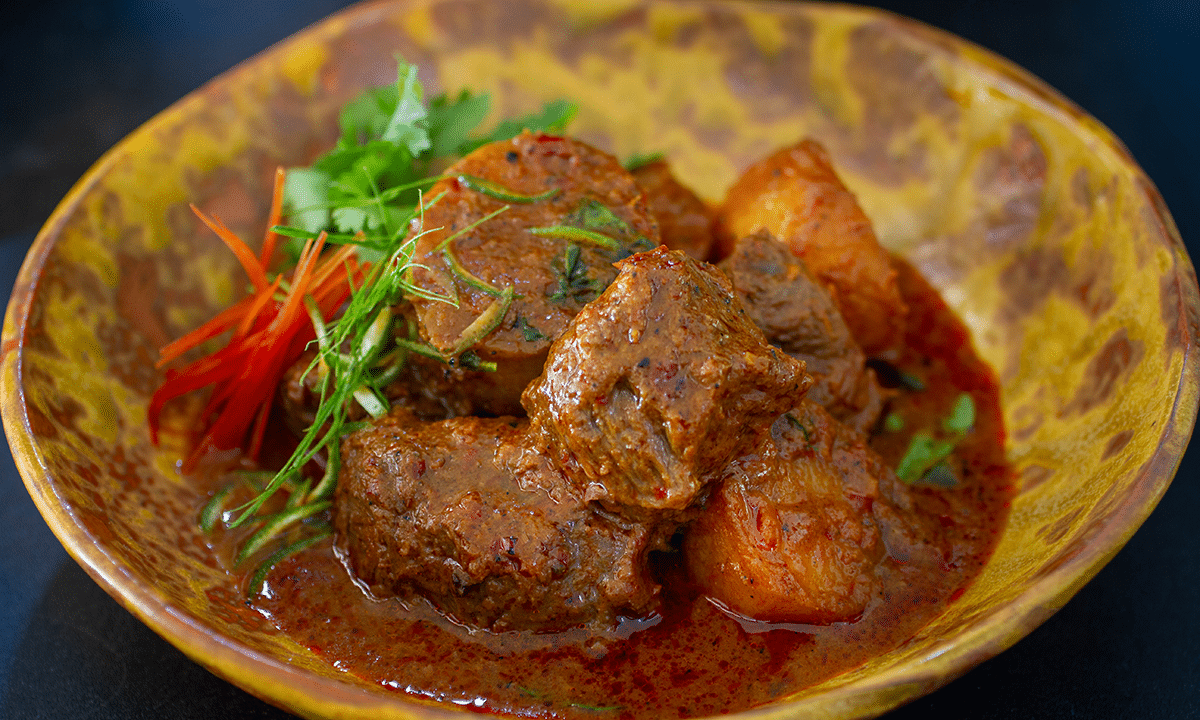

This magical floral and earthy coconut-based curry features stewed beef with saffron and young chilies. The curry’s golden color is reminiscent of glorious sunsets in the Persian salt desert and the great sand dunes of Rajasthan.

Unlike any other spice, saffron is strongly linked to the cultural and culinary identities of many of the nations that influenced the Siamese culinary repertoire as early as the Ayutthaya period, most notably the Persians, the Indians and, to a lesser extent, the Portuguese.