Heritage – Historical Siamese Culinary Manuscripts.

คลังตำราอาหารสยาม

A Thaifoodmaster Preservation Project

The Siamese Recipe Archive collects and translates historical Thai culinary manuscripts—primary sources written by the cooks, noblewomen, and food professionals who shaped the cuisine of the Rattanakosin era.

These are working documents. Each manuscript records practical knowledge shaped by its moment—what was available, what the tradition demanded, what a specific cook decided under real constraints. The sources vary—palace kitchens, professional caterers, schoolteachers, cremation volumes—but each preserves how someone approached the craft, the problems they solved, the techniques they considered worth recording.

Thaifoodmaster’s digitization projects make these texts accessible to modern cooks. We preserve the original authors’ voices—their instructions, their preferences, their occasional poetry—while converting archaic measurements to grams and presenting texts in readable modern formats.

The Archive Contains

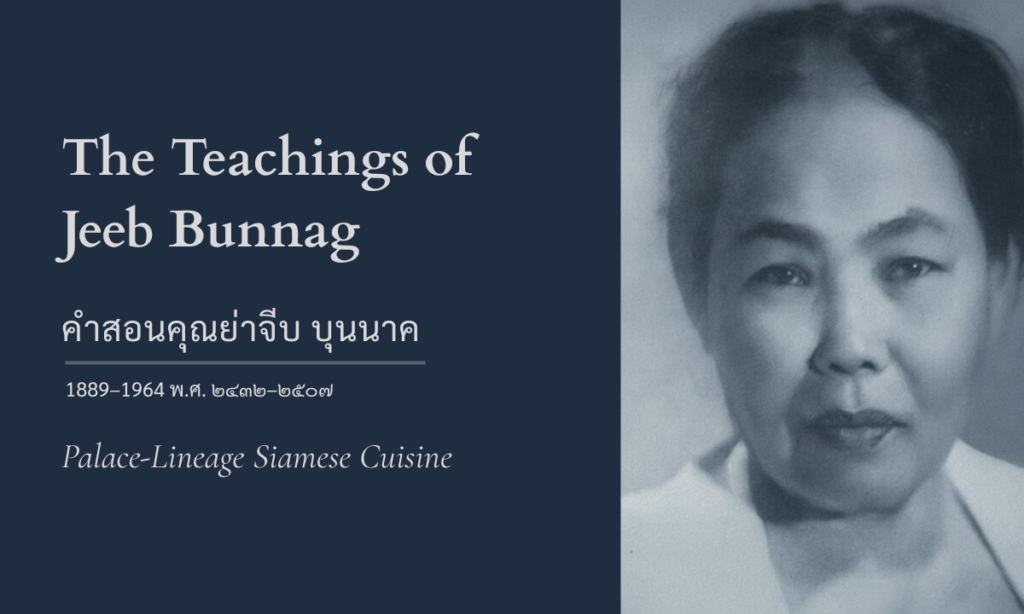

This archive gathers recipes from across her publications, spanning four decades from her 1933 Samrub Raawp Bpee (สำรับรอบปี) to works published after her death in 1964. Each preparation carries her teaching method—tested instructions, structural logic preserved, substitutions provided for those with dietary restrictions. Palace technique made accessible. Court cuisine adapted for household kitchens. The grammar of Siamese cooking recorded by someone who carried it by birthright and gave it away through teaching.

In her prefaces, she set out a philosophy: Thai cooking relies on estimation, on tasting and adjusting, on what she called roht meuu (รสมือ)—one’s delectable hands. Some cooks possess skill and knowledge of all ingredients, she wrote, yet lack “charm in the touch” (เสน่ห์ในรสมือ). Their cooking lacks deliciousness, lacks thoughtfulness, and fails to win appreciation from family and society.

Between 1949 and 1950, she published four books through Chamroen Sueksa (จำเริญศึกษา) in Bangkok: Thai salads, savory dishes, sweets, and a five-volume set spanning Thai, Chinese, and Western cooking. The table of contents reveal dishes with names shaped by court culture—Egg of the Moon (เครื่องเคียงไข่ดวงเดือน), Three Kings (เครื่องเคียงสามกษัตริย์), Pretending to Be Delicious (เครื่องจิ้มแสร้งว่าอร่อย). The identity behind the pen name may remain unknown. The recipes do not.

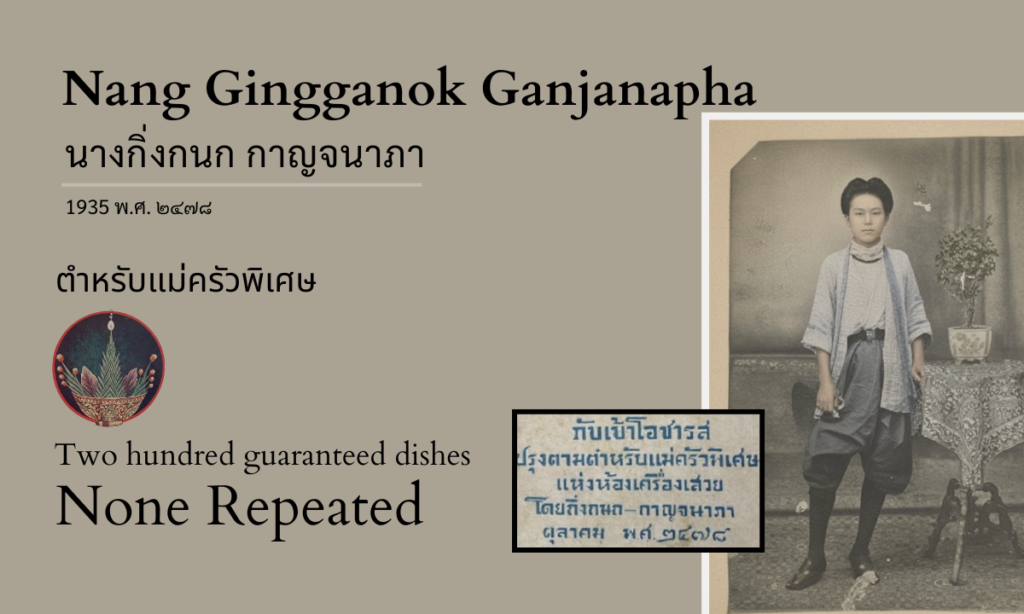

She wrote from a seaside house in Hua Hin (หัวหิน), completing the manuscript in July 1935 (พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘). Three women contributed to the compilation: Khun Praphai, Khun Jira, and Khun Noi—thanked for recipes “beyond her own ability to find.” The book appeared that October, priced at three baht.

No biographical record of Gingganok beyond this text has been located. The royal kitchen staff whose recipes fill the collection are not named. What survives is the cooking itself: technique, proportion, and method as these women understood royal kitchen practice in the mid-1930s.

She had researched and compiled cooking recipes (ตำราปรุงอาหาร), organizing them into categories as a household manual for her own use. Friends and fellow teachers (เพื่อนครู) urged her to publish, and she undertook further research to meet their expectations. Her sources were multiple: teachers and professors (ครูและอาจารย์), textbooks (ตำรา), explanations from those with expertise (ผู้ชำนาญ), and friends who shared her interest in cooking.

The series totals approximately 800 recipes across four volumes covering curries (แกง), salads (ยำ), stir-fries (ผัด), fried dishes (ทอด), dipping sauces (เครื่องจิ้ม), side dishes (เครื่องเคียง), snacks (ของว่าง), sweets (ของหวาน), and beverages (เครื่องดื่ม).

Every manuscript in this archive follows Thaifoodmaster’s preservation methodology:

Original voice intact. We translate what the author wrote, in the manner they wrote it. Instructions that seem unusual by modern standards remain as recorded. We do not edit for contemporary taste or convenience.

Measurements converted. Archaic Thai weight systems (chang, tamlung, baht, salueng) and volume measures (tanan, thanan yai) are converted to grams and milliliters. Original references are retained alongside conversions.

AI-assisted, human-verified. We use specially trained AI models (Jasmine, from ThaiFoodAI’s Flair and Spirit system) to process OCR and initial translation. Every document is examined before publication to ensure accuracy and cultural authenticity.

Why Primary Sources Matter

Modern Thai cookbooks interpret. Historical manuscripts record.

A 21st-century recipe for Gudee Curry (แกงกุดี) tells you how someone today thinks that dish should taste. Ibrahim Haji Roshidin Tuan’s 1938 instructions tell you how a professional Muslim caterer in Thonburi actually prepared it—the specific cuts of chicken, the ratio of ghee to coconut oil, the technique of sealing pot lids with flour paste for dum cooking.

Lady Plean Passakornrawong’s 1908 manuscript captures late-19th century Siamese cuisine before the culinary standardizations of the mid-20th century: ingredient varieties that have since disappeared, cooking vessels and fuel sources that shaped technique, market conditions that determined what was available and when.

These documents are fixed points. The soil has changed, the breeds have evolved, and jasmine-scented water no longer sits in earthenware jars. What remains are the authors’ recorded decisions—evidence of how Siamese cooks thought about flavor, technique, and presentation at specific historical moments.

About Thaifoodmaster

Thaifoodmaster was founded by Dr. Hanuman Aspler, a Thai food scholar who has lived in Thailand since 1989 and dedicated over 30 years to researching the history, culture, and techniques of Siamese cuisine.

Our mission is to promote the understanding, preservation, and dissemination of Thailand’s culinary heritage. We treat Thai cuisine as a language with its own grammar and lyrical quality—one that can be learned, understood, and eventually spoken with fluency and personal voice.

The Siamese Recipe Archive represents our commitment to primary-source access: making the original manuscripts available to professional chefs, culinary historians, and serious food enthusiasts who want to understand Thai cuisine at its roots.

Colorized presentation. Where original manuscripts survive only in deteriorated photographs, we apply digital colorization to restore visual clarity while preserving the printing-era aesthetics of each document.

Experience the authentic rhythm of traditional Siamese cooking.

Weekly Archive Dispatches

Each issue translates a fresh batch of recipes and opens with the manuscript behind them: who wrote it, when, from what kitchen and what position in Siamese food culture. The colorized folios — each page reconstructed from the original manuscript ink — are built for close reading and direct kitchen use.

Chefs develop menus from preparations and techniques that left the active repertoire decades ago. Home cooks gain a starting point grounded in primary sources. Researchers find what secondary literature rarely provides: fully attributed recipes tied to named authors, fixed dates, and documented manuscripts.

Where a historical cook left a step unwritten, the translation preserves that gap. The distance between their words and your plate — that is where your own cooking begins.

All issues are published here. Receive them by email.