By Jon Galpern

Hanuman excavates Thai culinary history through 19th-century cookbooks, uncovering a lost language of flavor. In his workshop 30 minutes outside Chiang Mai, I learned a dialect that the internet hasn’t managed to scrape—recipes and techniques that have been buried under a century of modernization.

The six-acre farm where Hanuman lives and teaches from didn’t always look like paradise. “It was a dump nobody wanted,” he tells me, pointing at rice fields stretching to the mountains. “See my neighbor’s horizon?” When he bought the land in 2013, it was a swamp two meters below the road. He drained it, uncovered a hidden natural spring, cleared the overgrowth, planted thousands of trees. Ten years later, it’s a lush property with 2,000 plant species—madan (sour cucumbers), white turmeric, ingredients most Westerners have never heard of—and at least seven dogs roaming between them, chasing birds and sounds through the garden.

It feels like entering someone’s realized fantasy, the I’m-going-to-leave-everything-behind-and-live-on-a-farm daydream, except he actually did it.

But Hanuman’s zen wasn’t always so palpable.

Hanuman was born in Israel. He graduated from medical school at age 23. At age 26, he called it quits on his medical career after visiting Bangkok in 1988. “I felt a special sense of peace in Thailand that I never felt in Israel.” He changed his name, Eyal, to Hanuman, and never looked back. In the 35+ years since leaving, he’s spent a collective 20 days in Israel.

Post medical career, Hanuman became a prominent gemologist; he co-founded Ganoksin, the oldest and largest online community for the jewelry trade. During that time, Hanuman had developed an obsessive collecting habit. He couldn’t walk home without stopping in an antique shop, spending hours, and leaving with a few new finds.

Everything changed in 2011, after the Thailand floods.

He showed us pictures of his old Bangkok home during the great floods—45 days underwater, the first floor transformed into a Venetian canal where he rowed a boat out of his living room. He lost prized furniture and antiques. It took almost two months to clear all the water out and restore it.

Despite the home’s restoration, he suddenly felt divorced from the house and the things inside. “At first, five minutes of sadness,” he shrugged. “Then I realized happiness isn’t in the stuff. You get five minutes of joy when you buy it, five minutes of sadness when you lose it. That’s it. Better to choose how you spend your energy.”

When you enter Three Trees farm today, you can sense the changed man. The home’s interior is minimalist and functional. Little to no art decorates the walls. The walls are painted white, the wooden furniture appears homemade; there’s not a splash of eccentricity in sight. The only antiques I noticed are the cookbooks. Hanuman himself wears the same outfit every day: black tee with his farm logo, black pants, black slip-ons.

The journey from gemology to ThaiFoodMaster didn’t happen overnight. It didn’t follow a traditional culinary path. He never worked in a restaurant or attended cooking school. In this interview he states, “I learnt to cook the food I loved first because I thought this would be the only way to keep the flavours with me, if anything happened and I had to leave the country… Friends in Bangkok would come over and I would show them simple recipes in our kitchen, and I enjoyed spending time with them. In the beginning the idea was formed but not fully realised.”

I kept trying to pin down the exact moment when the surgeon turned jeweler/gemologist, then turned chef? He’d wave the question away, all he said was that in the 2010s he gained notoriety for blog posts detailing how Westerners could cook Thai food well. Maybe the transition was so gradual he doesn’t see a clean break. Or maybe, like the flood that stripped away his attachment to objects, he’s also let go of his attachment to his former self. He doesn’t want to curate his own origin story.

The Workshop

When I first arrived in Thailand, I had initially planned to do a month-long intensive at the Bangkok Cooking Academy. Before committing, I signed up for a few days. It was fine, but taught me nothing I couldn’t learn free from the excellent Pallin’s Kitchen YouTube channel. This felt like a glorified extended AirBnB experience cooking class of recipe-following masquerading as a professional cooking academy, handing you a diploma at the end because that makes it professional.

Hanuman’s workshop stood in stark contrast. Through his reading of 19th century cookbooks, he’s revealing past ways of communication. To him, cooking is a language. His commitment to the language extends to the point of replicating Siam’s centuries-old model of obtaining and cooking ingredients from around the farm. Resulting in an experience that can’t be replicated nor commoditized.

His workshop teaches 1-4 students at a time, students take anywhere from a few days of classes to a month of training. He’s taught everyone from Michelin-rated chefs to personal chefs to home cooks like yours truly. The daily rate was roughly $300 USD. I did eight days with two other students. Both were professional chefs with Thai origins. Ty is a personal chef in San Francisco with aspirations to start his own Thai restaurant in America, while Kay is in the process of opening a Thai cafe in Australia.

Ty is in his 30s. Immaculate fade haircut. Extremely diligent; takes copious notes. He generously answered my questions, “Is this the correct order of curry paste pounding operations? Am I pounding right? Does the paste look properly pounded now?” We loved tasting each meal to our heart’s content and stomach’s discomfort.

Kay is in his mid 20s. Baby-faced yet confident. Fast. Creative. Erratic. Minces like it’s a Top Chef competition, yet zones out during wok frying duty before locking back in for dish presentation. Like a Jenga pro, he carefully stacks the red, yellow and green matchstick-sliced chilis to the top of the Miang Santol tower, and bunches up the cowslip creeper leaves to the back.

In between curry bites, Kay loved to munch on bird’s eye chilis and cucumbers. One day he nonchalantly handed me quite a few chilis for my enjoyment. He subtly glanced my way, struggling to hide his smirk in anticipation of my post-chili-bite face. I was unfazed though. I had a month of Bangkok eating under my belt to build up my spice tolerance. Sorry Kay.

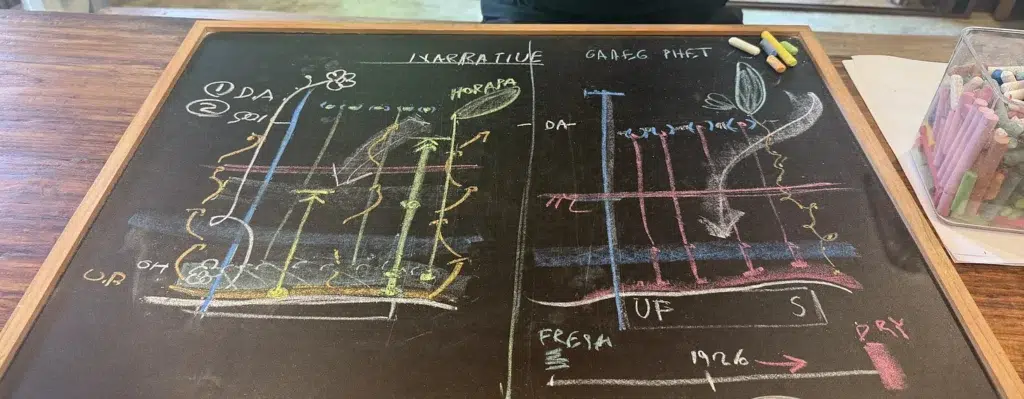

Before cooking, we all sat on the patio table. Hanuman would bust out a chalkboard and lecture us on each recipe’s history. Every five minutes, I’d turn left to relish the view of the natural spring and jungle trees on the horizon..

One day we engaged in a debate over Lady Gleep Mahithaawn’s 1949 recipe for “rice noodles with chicken and aromatic coconut sauce.” The recipe asked for the chicken meat to be “sliced thinly, almost minced.” That sparked an entire philosophical riff from Hanuman. He stated “mincing = chaos and pain, slicing = order. Almost minced exists in a liminal zone—neither palace refinement nor rustic roughness, but something in between. To replicate her recipe, you must think like her, channeling her hybrid identity of palace finesse + rural frugality.” This shows how recipes are not just instructions but cultural, personal, even psychological imprints.

Hanuman incorporates the historical with the science of cooking and from that he creates methodologies that are both unique to Thai cuisine, yet also apply to cooking in general. His goal isn’t for you to follow recipes. It is for you to learn how to provide your own perspective. Hanuman challenges us to think about the history of a dish and our own interpretation. “How do you want to approach it? What ingredients do you want to add or remove?” The only wrong answer is not having a perspective.

For him, perspective means creating patterns that connect. Eating, he says, is a multidimensional experience of taste and aroma, so a chef must build depth. If shrimp is your main feature, you might create a triad: grilled shrimp, dried shrimp, fermented shrimp paste. Each bite hits the brain differently, making the dish dynamic and alive. Tie those ideas together with as many “habitats” as possible— air, land, and sea — infusing chicken stock (air) with dried shrimp (sea) and coriander (land).

Hanuman balances science with story. On a crab curry recipe, he turned to color as narrative. “The color should represent your dreams,” he said. “When you close your eyes, that’s what you want to reflect. Sunset, sand, the memory of love… it doesn’t matter, as long as it’s deliberate, not accidental. Every curry offers a painter’s decision. With the same paste, you can push it yellow with turmeric, orange with turmeric plus red chilis, green with fresh chilis, brown with roasted ones.” When you toss in that crab, he says, name it. Define it. Someone might feel the perspective you’re bringing. Call it a “memory,” and maybe the eater will taste that, too.

You learn secrets on flavor-enhancing techniques and the science behind it. Ingredients like galangal and ginger generate saliva in your mouth when chewing, bringing flavors into slow motion, so you can better taste the complexity of your dish. When frying the curry paste, he had us toss a tiny pinch of toasted cumin seed and coriander every ten seconds to create an aromatic flavor trail called “Hansel and Gretel.” A flavor trail creates depth; a breadcrumb of timed flavor releases, where the surprise reappearance of cumin and coriander into every chew creates that essential 3D experience. Instead of flat, the 3–10 seconds you chew become very complex.

After discussing the recipes we’d go into the small eight-burner kitchen. Ty, Kay, and I stood side by side with our circular wooden cutting board, knife, and mortar and pestle. On occasion, I found myself bumping into one of the two lovely elderly Thai women standing to the left of me hovering over the kitchen sink. They quietly and efficiently clean dishes at all times and pass the clean items back to us ‘hot potato’ style. The kitchen was stuffed with homemade chili jams, 10-year aged fish sauces, and endless supplies of freshly picked lemongrass, galangal, turmeric. Everything inside was Hanuman’s personal expression. You were stepping into his life’s work, not just a kitchen.

Hanuman brings lightness into the cooking process. His natural inclination is to be silly. For the entire week, he found endless joy in shouting ‘khráp thâan’—Thai for ‘yes, sir’—whenever you asked him for anything. He’d shout it over and over again, giggling like a schoolboy. When giving frying instructions, he’d grin and say, ‘I want it fried golden—like a Swedish girl on the beach,’ a line he repeated with mischievous glee.

Pokpokpokpokpok. A pestle ricochets against mortar at all times. The foundation of every Thai curry starts here. Thai cooking isn’t throw-everything-into-a-pot cuisine. Cooking for more people = more time pounding paste. A mortar and pestle tests your patience. It’s exhausting work. And when you pound for restaurant quality it’s gotta be smooth, you can’t have a loose fibrous piece of galangal in your paste.

When plating a dish, Hanuman would step outside to his ceramic dish storage shed. He’d analyze the hundreds of plates available, pick out the perfect ones, plate the dish with surgical precision, and set his phone on portrait mode to commemorate the moment.

Before tasting, he wanted us to be incredibly mindful with those first few bites. He said “you should name your feelings, and let loose your associations. It should remind you of something.” If you’re tasting a dish for the first time, you’re creating a file in your brain. For example, if you’re tasting Khao Soi for the first time, well that’s going to be your reference point going forward. You’ll compare every future Khao Soi to that first tasting. The next version becomes a subfolder under your Khao Soi master file. In eight days, I created 25+ master files. The food we made spoiled me. There are many dishes I know I will likely never taste again, or it certainly won’t taste the same.

One day we made naam phrik long reuaa (boat embarking chili relish, fermented shrimp paste chili relish with sweet pork condiment). The deep-fried catfish floated in the paste, looking like gold coral if gold coral got plastic surgery to get thicc—all puffed ridges and bronze crust. The first bite felt like stepping on leaves in a Pacific Northwest forest. The fermented shrimp paste and sweet pork created a funky-sweet base, cut by pickled garlic that snapped like twigs underfoot and salted duck egg that spread its time-earned orange yolk wisdom across every bite. The whole dish tasted like that moment on a coastal trail when the forest floor meets the ocean breeze.

There’s one dish, duck sa weeuy, that remains hazy in my master file. It was a spicy duck curry recipe from 1941 by Thanom Palaboot. I was tired of pounding, in a rush to arrive at my non-pounding future self. I absently moved through the steps. This happened on day three. The thing is, by day three, I had already learned how to properly make curry. For mise-en-place, we’d organize ingredients on a metal tray. Hanuman taught us to prepare more ingredients than necessary on your tray before adjusting accordingly during the pounding process. Then we’d follow our universal curry ratios, like when dried long red chilis are used, the amount of lemongrass should be half that of the chilis. Galangal should be half the amount of lemongrass, and so on.

I had blanked out and didn’t measure the proper ratio of ingredients to actually pound. Everything from the tray went directly into the mortar. For curries, you season during the curry paste frying portion. You use fish sauce, tamarind, and palm sugar for seasoning. In Thai cooking, you rarely use coarse salt. Fish sauce is your salt. Tamarind is your sour. Palm sugar is your sweet. Upon frying, Hanuman tasted my curry. He winced. “You used triple the amount of spices.” No amount of seasoning could fix my spicing.

He said, “It’s okay. It’s only food.” A funny statement though. I understand the sentiment. But it’s also the thing he’s dedicated his life to. “Is it only food?” Despite his kindness, I felt terrible that whole day. I hated that neither I nor my fellow students would get to experience how that curry was supposed to taste. Kay wasn’t with us that day, but Ty tasted the dish, kindly reserved any comments, and instead stuffed his face with the Thai Javanese curry he flawlessly executed.

Kay and Ty didn’t struggle with anything. Well Kay struggled with focus if anything, hello Gen Z. But that’s a different skill issue. Hanuman relegated me to matchstick slicing, garlic peeling duty, and the “so easy a caveman can do it” task of pounding curry paste. Except not so easy because Hanuman circled back twice on separate days to reteach me the proper way to lay the pestle down, son.

By the evening of day three, I gave myself grace. It made sense that this mistake happened then. During the first few days, the dopamine rush of learning carries you to the end. Everything is new and exciting. It’s easy to be present every step of the way. By day three, I was creating variations of a now learned foundation. I was learning subtle things, like substituting white turmeric for orange or using rehydrated chilis over dried ones. When novelty fades, your mind wanders. It feels the impulse to rush through steps so you can move onto the next dopamine-inducing challenge.

I’ve made this mistake countless times in my life. I’ve done it in this essay –by the third draft, I catch myself reaching for my phone constantly instead of pushing through to the next sentence. I started writing this in late September, and have avoided the challenge of polishing this for publication. When I let the task’s discomfort take control, I wind up overspicing a curry or leaving words unwritten.

The Art of Attention

After day three’s failure, I made a vow to remind myself to be more present. To practice paying attention. To the feeling I was having while cooking. To stop looking ahead to the end of a task. From day four onward I challenged myself to notice more throughout each task—the bubbles that rise from frying curry paste, the satisfaction of well-sliced matching matchsticks, the silent art of dish presentation. I found myself relishing the repetition of peeling endless amounts of garlic, ginger, and galangal. I made fewer mistakes. My curries got better. My brain turned off during the tasks at hand, lost in flow. It was a wonderful respite from my brain’s constant chatter.

I’ve concluded almost five months of travel. I’ve seen everything from the Sahara Desert, Northern Thailand jungles, Bali beaches, and experienced city life in Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, and Tokyo. It’s been a blast, but I can’t help the feeling that with each new place I have to fight harder for enjoyment. Cities start to blend together. It’s harder to be surprised. The challenge is maintaining your curiosity, and not let yourself grow numb by the sameness.

In Tokyo my expat friend hosted a picnic. There I met a wise 20-year-old Gen Z Vietnamese friend, Charlie, who shockingly speaks perfect California accented English thanks to Discord and watching Smosh. She told me, “I used to put myself in events like this picnic just to be in it and have my mind constantly asking ‘what’s next?’ instead of ‘what’s happening?’”

Moving forward as the novelty of experiences continues to fade, the next chapter for me is to practice the art of mindfully engaging, slowing things down, and truly immersing myself into the taste of every moment.

Hanuman’s class taught me how to savor. It made me realize how much more there is to learn and appreciate in cooking. I know salt, acid, fat, heat, but I don’t know the history of nearly any dish I’ve ever cooked. Before Hanuman, my relationship to cooking was simple. I bought cookbooks from chefs I admired and cooked family recipes.

A few years ago I built a barbacoa pit in my backyard to connect with my late grandfather. He had a ranch in Monterrey, Mexico where he’d host barbacoa cookouts. I never got to attend, but my father would regale me with stories of those gatherings. My grandfather would leave the cooking to others, while he’d sleep outside next to the pit to make sure everything was ready by morning.

Despite digging a 4×4 foot hole and hosting these 35+ pound meat cookouts several times, I never looked beyond the familial connection. After Hanuman’s class, I looked up the history of barbacoa: how it stems from prehistoric times, how it’s a spiritual practice in some regions. I learned how the Spanish influenced it with their spices, how the Mayans placed the food on altars as offerings to the deceased.

Hanuman’s class taught me to look beyond myself and my family, to the entire cultural footprint of a dish. With him, I discovered a new perspective to apply to future cooking and an appreciation that extends beyond recipes. It’s forever changed my relationship to cooking.

By dawn tomorrow, Hanuman will be up again, reading another century-old cookbook by the lake. I’m still tracing his flavor trails in the kitchen and beyond.

Jon Galpern – Ex-marketing director, now making things for the joy of it. Personal essays on leaving corporate life, traveling solo, and learning to play again.