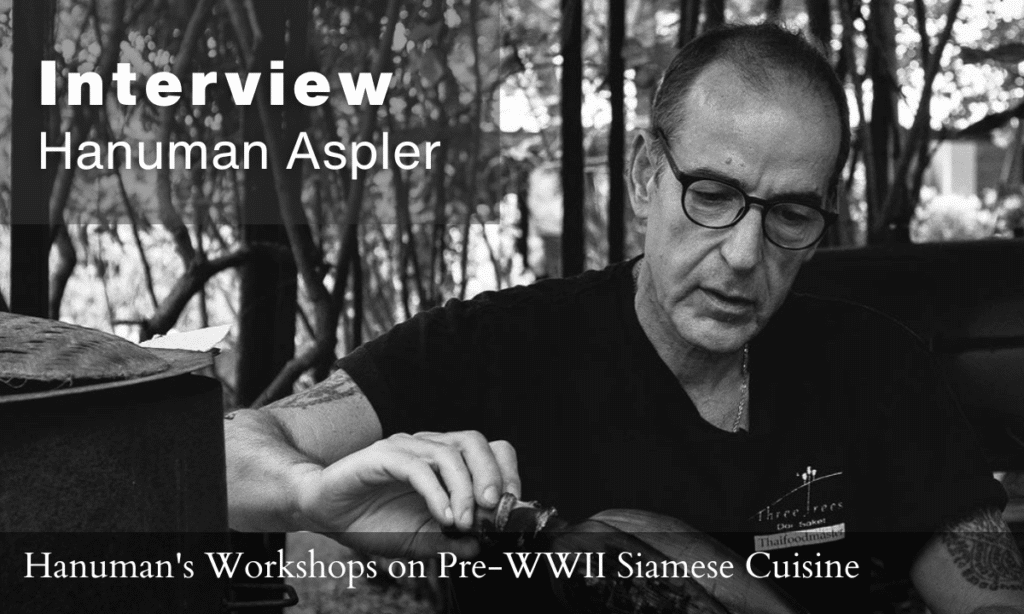

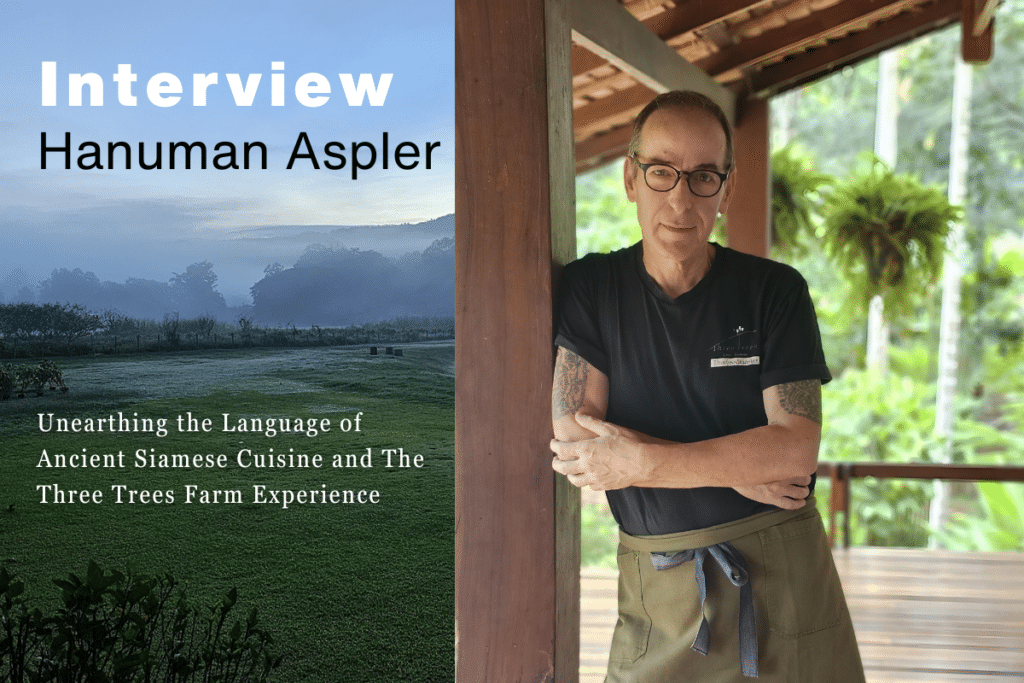

In this revealing interview, Asha Tanna sits down with Hanuman Aspler to explore his one-of-a-kind philosophy on Thai cooking. Located a mere 40 minutes from central Chiang Mai, Hanuman’s Three Trees Farm offers more than just a cooking class—it provides an education in ancient Siamese cuisine. But Hanuman isn’t interested in merely passing on recipes. Drawing from old manuscripts, he treats Thai cooking as a language with its own set of rules and syntax. His unique blend of historical understanding and hands-on practice makes his teaching style a standout in Thailand’s culinary scene. Continue reading to delve into his unique approach.

By Asha Tanna

Taking a culinary course at Three Trees Doi Saket in northern Thailand, is like opening a time capsule to ancient Siamese cuisine.

Guiding you through that unique experience is Hanuman Aspler, a 61-year-old Israeli-born Thai Food Master, whose passion and intrigue lies in ancient manuscripts.

“In order to understand Thai modern cuisine you have to have context. You have to be able to reflect on things by looking at the past. This is logical.

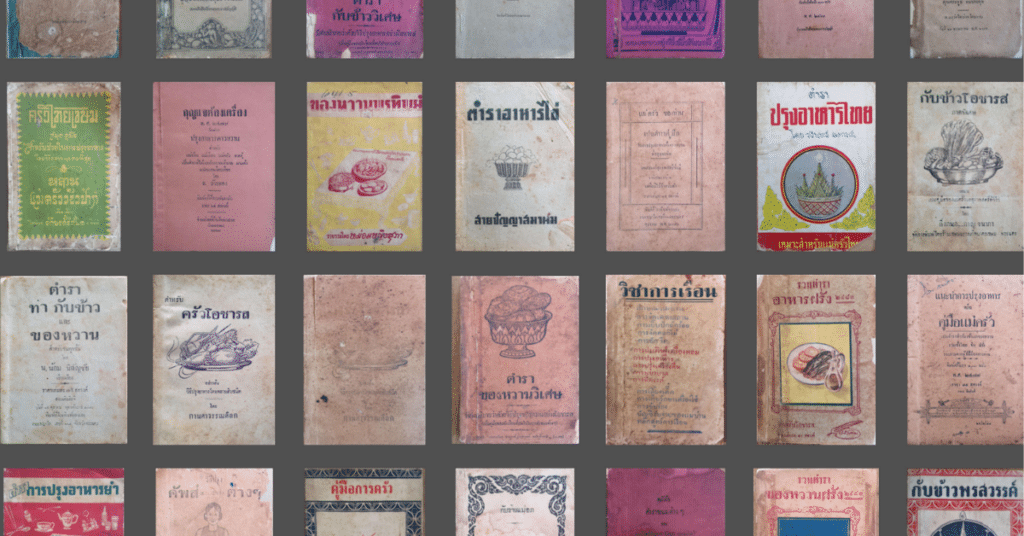

“Food is not a combination of a few words or patterns, it is a language. That’s why I go to the old books and manuscripts.”

No other culinary school in the country offers this unparalleled journey, he says, it brings together Thailand’s culturally rich and historical past and links it to regional recipes. Using his own “tried-and-tested formula” Hanuman coaches his students to have an analytical approach to each dish.

“I can get someone to cook Thai food reasonably well in 12 days because I have created a language. I am going to get you to think, create and find your own voice, this is not how to cook. It is a hunt for patterns and combinations and how the elements are blending or not blending.”

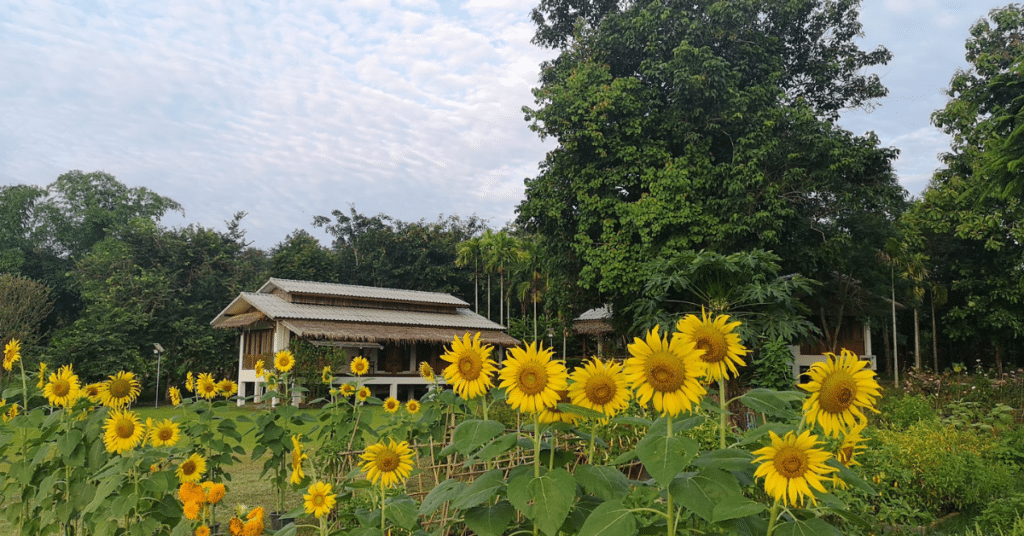

His farm and cooking school have been a labour of love in the making. The land was bought in 2013 and the house was eventually finished in 2017.

“We are view addicts,” he says, gesturing to his Thai partner, Ton. The pair quit the hedonistic city life of Bangkok a decade ago in search of something more holistic.

“We decided to try to live a simple life in the mountains. So we started looking at land. We wanted a place with gardens and more connection to nature. But we are also both city people and we didn’t know if we could live like that, it was a gamble.”

The gamble paid off. Three Trees Doi Saket is set onto six and a half acres of lush green tropical vegetation, 40 minutes from central Chiang Mai. The spacious and airy property is surrounded by 2000 different flora, which took six months to collect. Landscape gardening is another of Hanuman’s talents; and almost all the herbs and plants students cook with are sourced on site.

“Nearly all the ingredients can be obtained from around the home as was common in Siam for so many centuries. What we do is teach the language of the manuscript so that it makes sense and then we can use those ancient books to revive recipes.

“When you read an ancient text it is awkward. They didn’t have a template. They tried following the British model of cookery books that were around and after that they tried to standardise weight by pieces. Some use traditional Thai measurements and sometimes no measurements.”

On teaching days the constant clinking of the granite mortars and pestles echo throughout the property, as students set about pounding and grinding down their ingredients. Banter and fun anecdotes fill the small, compact kitchen that also looks onto the impressive and well-manicured garden. It is an intimate space for creating.

There is an idyllic pond in the grounds, Chiang Mai’s mountains give a dramatic backdrop and the sound of wildlife is everywhere, making it the perfect location for a “fully immersed Thai cooking experience,” he says.

“We treated the project like we were growing a seed and we wanted to be part of the process. We didn’t want to leave it in the hands of someone else. For five years we would come up from central Chiang Mai for a week, each month, and sit on daybeds and listen to the birds, see where the sun would come from, and experience what it was like at night. We knew what we were aiming for.”

Today Hanuman’s tools in his kitchen are very different to the ones he started with. Back in Israel he trained and worked as a physician (Dr Eyal Aspler) in Tel Aviv. But after the death of his father, Isaac, he decided it was now or never to explore his dreams.

He landed in Bangkok in 1988, changed his name, and fell in love with Thai food from his first bite, especially curried stir fried wild boar (Pad Phet Moo Pa).

“I learnt to cook the food I loved first because I thought this would be the only way to keep the flavours with me, if anything happened and I had to leave the country. The first dish I learnt to cook was stir fried chicken liver with holy basil (Pad Kra Pao Tab Gai). Friends in Bangkok would come over and I would show them simple recipes in our kitchen, and I enjoyed spending time with them. In the beginning the idea was formed but not fully realised.”

His late father used to say “Do something you can eat with,” the irony of those words are not lost on Hanuman, who has taught more than 500 people since opening his school. These include Michelin-starred Thai chefs as well as foreign chefs world-wide. The testimonials read like a who’s who from the hospitality industry. But the school is not exclusively aimed at professional chefs, it is open to anyone, skilled or not, with a passion to learn and create Thai food. His workshops are customised for every client.

“The idea is that the participant will find their own voice. Not to cook like I did, or how the people in ancient times did, but to have the confidence to make their own signature.

“We touch the soul and heart through food. I know that sounds clichéd, but we dive deep into the purest way of cooking.”

It was not until 2008 that he shifted his concentration towards ancient Siamese cooking. A heart-attack pushed him to re-evaluate his lifestyle, “I was doing too much drinking and smoking and that triggered the daily cooking and deep research, so yes it was a pivotal moment.”

Ancient Siamese cuisine pulled together the knowledge of cooks from every level of society, from housewives, to cooks in the temple, to the culinary masters who created elaborate dishes behind the palace walls, he says. Creating dishes linked to the past is also an educational experience.

“I always loved to cook more than I loved to eat. I sit and read and write about food all day – it is an elaborate understanding of how food is connected and what it is telling us.

“When I read the books I try to visualise the era in 3D. I think about how the markets were at the time and how people then would see it. I have come up with a system that works. The old books give me comfort like a family I never had, the grandmother and aunties. I read the recipes again and again and again and I get comfort from them.”

These days Hanuman digitises the pages of the old manuscripts so that he can read them often and the rest of his precious collection are in his library. But finding ancient books is harder than you think.

“Anyone who collects old books will tell you, the book will find you. Not the other way around,” he chuckles.

“Recently I had two 24-year-old Thai students come to me. To have two young kids, to shape them, makes me happy to give them the tools to excel. I don’t think the information I hold belongs to me, I believe it should be in the public domain.”

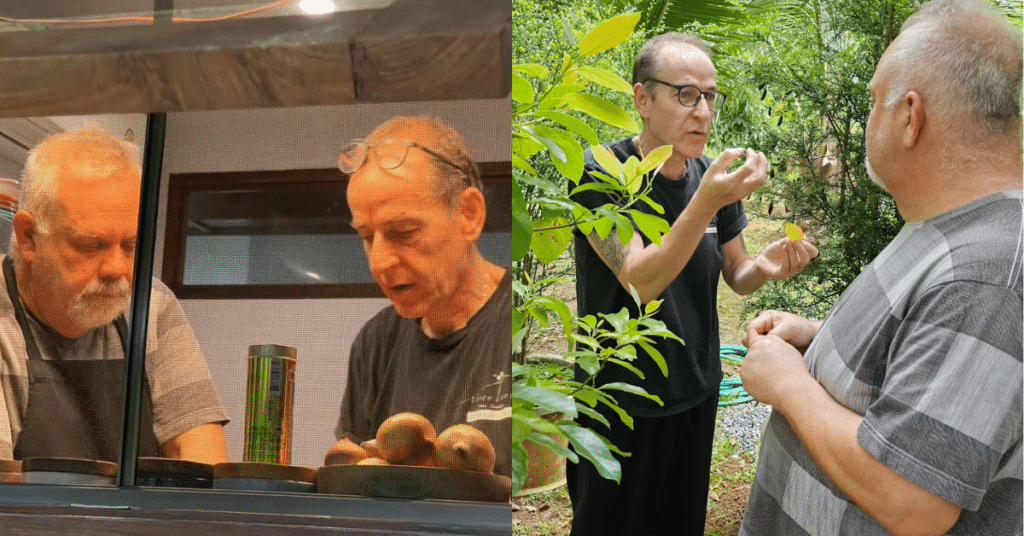

The conveyor belt of students coming to the farm to learn from the Thai Food Master is endless. Most recently a very famous chef from Israel, Ran Shmueli.

“When you get a chef like that, who is at a certain level, they tend to come here to get inspired and to learn something new. They never thought being here will teach them something new. It is wonderful to see.

“For me it’s like a triangle: in order to learn I need to practice, and in order to practice I need to teach. If I have a complex problem, I need to teach to understand it.”

When he looks back at his journey he says not everyone was supportive.

“There were people back home in the beginning who thought I was off my rail and that I needed an intervention. Everyone who knew me thought I was flushing my life down the drain. Everyone put pressure on me to go back, but not my mother, Hava. She understood and yes, she is proud of my achievements.

“For the naysayers, now everybody can see what I was aiming for. If my father was alive today he would probably say ‘you have more luck than brain,’.

“Today there is a real deep satisfaction being here. I still have moments where I ask myself, ‘Did we do this?’ it always hits me,” he says smiling broadly.

For more information on how to book classes at Three Trees Doi Saket click here.

Asha Tanna is a retired British journalist, now living in Chiang Mai, Thailand

Related: