What’s New on Thaifoodmaster

Daily Folios from the Siamese Recipe Archive

Historical manuscript translations

Explore the Heritage Archive

Project

December 2025

The Teachings of Jeeb Bunnag (คำสอนคุณย่าจีบ บุนนาค)

In 1929, fire destroyed her home in Bang Krabue—manuscripts, possessions, the material inheritance of generations. What survived was knowledge. Trained by Lady Plean Passakornrawong in the palace kitchens, she carried a culinary tradition that could not burn. Four years later, she began publishing. She signed her books with her actual address so anyone could write to her.

This archive gathers recipes from across her publications, spanning four decades from her 1933 Samrub Raawp Bpee (สำรับรอบปี) to works published after her death in 1964. Each preparation carries her teaching method—tested instructions, structural logic preserved, substitutions provided for those with dietary restrictions. Palace technique made accessible. Court cuisine adapted for household kitchens. The grammar of Siamese cooking recorded by someone who carried it by birthright and gave it away through teaching.

This archive gathers recipes from across her publications, spanning four decades from her 1933 Samrub Raawp Bpee (สำรับรอบปี) to works published after her death in 1964. Each preparation carries her teaching method—tested instructions, structural logic preserved, substitutions provided for those with dietary restrictions. Palace technique made accessible. Court cuisine adapted for household kitchens. The grammar of Siamese cooking recorded by someone who carried it by birthright and gave it away through teaching.

Project

December 2025

The Islamic Cook & The Muslim Cook (ตำราพ่อครัวอิสลาม และ แม่ครัวมุสลิม)

Recipes from Thailand’s first documented Thai-Muslim cookbook, published by Ibrahim Haji Roshidin Tuan (อิบรอฮิม หะยี รอซีดีน ตวน) of Thonburi. The collection originated in 1929 as “The Islamic Cook” (ตำราพ่อครัวอิสลาม), later expanded in 1938 as “The Muslim Cook” (แม่ครัวมุสลิม). Ibrahim was a professional caterer working weddings, funerals, and hired events—his recipes specify quantities for feeding crowds and preserve techniques from working Thai-Muslim kitchens of the era.

Project

December 2025

Heritage – Historical Siamese Culinary Manuscripts (คลังตำราอาหารสยาม)

A Thaifoodmaster Preservation Project

The Siamese Recipe Archive collects and translates historical Thai culinary manuscripts-primary sources written by the cooks, noblewomen, and food professionals who shaped the cuisine of the Rattanakosin era.

These are working documents. Each manuscript records practical knowledge shaped by its moment-what was available, what the tradition demanded, what a specific cook decided under real constraints. The sources vary -palace kitchens, professional caterers, schoolteachers, cremation volumes-but each preserves how someone approached the craft, the problems they solved, the techniques they considered worth recording.

Thaifoodmaster’s digitization projects make these texts accessible to modern cooks. We preserve the original authors’ voices-their instructions, their preferences, their occasional poetry-while converting archaic measurements to grams and presenting texts in readable modern formats.

The Siamese Recipe Archive collects and translates historical Thai culinary manuscripts-primary sources written by the cooks, noblewomen, and food professionals who shaped the cuisine of the Rattanakosin era.

These are working documents. Each manuscript records practical knowledge shaped by its moment-what was available, what the tradition demanded, what a specific cook decided under real constraints. The sources vary -palace kitchens, professional caterers, schoolteachers, cremation volumes-but each preserves how someone approached the craft, the problems they solved, the techniques they considered worth recording.

Thaifoodmaster’s digitization projects make these texts accessible to modern cooks. We preserve the original authors’ voices-their instructions, their preferences, their occasional poetry-while converting archaic measurements to grams and presenting texts in readable modern formats.

Article

December 2025

Learning Thai Cooking from a Culinary Archaeologist – Eight Days of Cooking in Chiang Mai

Hanuman excavates Thai culinary history through 19th-century cookbooks, uncovering a lost language of flavor. In his workshop 30 minutes outside Chiang Mai, I learned a dialect that the internet hasn’t managed to scrape—recipes and techniques that have been buried under a century of modernization.

The six-acre farm where Hanuman lives and teaches from didn’t always look like paradise. “It was a dump nobody wanted,” he tells me, pointing at rice fields stretching to the mountains. “See my neighbor’s horizon?” When he bought the land in 2013, it was a swamp two meters below the road. He drained it, uncovered a hidden natural spring, cleared the overgrowth, planted thousands of trees. Ten years later, it’s a lush property with 2,000 plant species—madan (sour cucumbers), white turmeric, ingredients most Westerners have never heard of—and at least seven dogs roaming between them, chasing birds and sounds through the garden.

It feels like entering someone’s realized fantasy, the I’m-going-to-leave-everything-behind-and-live-on-a-farm daydream, except he actually did it.

The six-acre farm where Hanuman lives and teaches from didn’t always look like paradise. “It was a dump nobody wanted,” he tells me, pointing at rice fields stretching to the mountains. “See my neighbor’s horizon?” When he bought the land in 2013, it was a swamp two meters below the road. He drained it, uncovered a hidden natural spring, cleared the overgrowth, planted thousands of trees. Ten years later, it’s a lush property with 2,000 plant species—madan (sour cucumbers), white turmeric, ingredients most Westerners have never heard of—and at least seven dogs roaming between them, chasing birds and sounds through the garden.

It feels like entering someone’s realized fantasy, the I’m-going-to-leave-everything-behind-and-live-on-a-farm daydream, except he actually did it.

Recipe

September 2025

c1935 Trinarong Salad – Thai Three-Fruit Yam from Pathum Thani (ยำตรีณรงค์; yam dtreen rohng)

Three fruits, three proteins, one extraordinary salad preserved in a funeral cookbook from provincial Thailand. This jewel-like dish combines pomelo, rose apple, and pomegranate with river shrimp, chicken, and pork—all dressed in the classic sour-salty-sweet dressing.

From Ms. Booree Thohnsak’s 1935 memorial cookbook, when Pathum Thani gardens provided everything within walking distance. The same afternoon light that made her pomegranate seeds glow like rubies will illuminate yours too.

From Ms. Booree Thohnsak’s 1935 memorial cookbook, when Pathum Thani gardens provided everything within walking distance. The same afternoon light that made her pomegranate seeds glow like rubies will illuminate yours too.

Article

September 2025

How to Read Historical Recipes: A Four-Dimensional Approach to Siamese Culinary

Every chef attempting to resurrect historical Siamese recipes confronts an uncomfortable truth: perfect replication is impossible. The soil has shifted its mineral composition since the 1890s. Heritage breeds have evolved. Even water tastes different now, filtered through treatment plants rather than stored in earthenware jars perfumed with jasmine flowers and pandan leaves. Yet this impossibility becomes liberation once we reframe what recipes actually are—not fixed instructions but ranges of potential outcomes that crystallize through cooking and transform into lived experience through eating. Historical recipes require four-dimensional reading: literal, contextual, subtextual, and narrative. They answer to four governors: availability, cultural appropriateness, culinary tradition, and superstition. Understanding these frameworks reveals where creative freedom genuinely lies—in that fertile space between memory and imagination where you construct your own culinary narrative. We’re not archaeologists trying to resurrect dead dishes but active participants in living traditions.

Masterclass

August 2025

Aromatic Primer for Thai Cuisine – Part 1

How our bodies detect and process aroma through taste receptors, smell pathways, and temperature sensors—the biological and chemical foundations for developing precise aromatic language. This essential science reveals why your brain can’t distinguish between chilies and actual heat, how fat and starch control aroma timing, when salt and acid trigger volatile release, and why cultural exposure physically rewires perception. Master these mechanisms first—then you can learn to name, control, and teach what you smell in Thai cuisine.

Recipe

Article

August 2025

c1933 khuaa Curry with Bang Chang Chilies (แกงคั่วพริกขี้หนูหรือพริกชี้ฟ้า; gaaeng khuaa phrik baang chaang): Princess Dissakul’s Smoky Fish Curry Recipe

Princess Dissakul’s 1933 royal Thai curry featuring secretly pounded smoked fish in rich coconut cream with Bang Chang chilies and aromatic phrik khing paste. This complex, smoky curry builds layers of earth and ember, traditionally served over khanom jeen fermented rice noodles and topped with tangy pickled garlic for a perfect balance of smoke, spice, and tang.

Recipe

Article

August 2025

c1935 Princess Yaovabha’s Sweet Chinese Sausage in Coconut Cream Soup (แกงไส้กรอกหมูแห้ง; gaaeng sai graawk muu haaeng)

A 1935 Thai palace recipe from Princess Yaovabha’s cookbook Sai Yaowapa, this Chinese sausage coconut soup represents a historic culinary transformation. Sweet goon chiang sausages float in an ivory pool of coconut cream, offering a lightly sour, lightly salty flavor with lemongrass, bruised shallots, and sour fruits. Once considered too common for aristocratic tables, Chinese sausage and other preserved meats earned their place in royal Thai cuisine by the 1930s. This comforting soup showcases the elegant fusion of Thai palace cooking with Chinese preserved meats.

Recipe

Article

August 2025

Yogurt-Based Ancient Green Curry with Chicken Offal (แกงเขียว; gaaeng khiaao)

Mrs. Yim Pichaiyat Bunnag’s 1920s aristocratic green curry reveals a forgotten chapter in Thai culinary history. This Muslim-style recipe uses ghee and yogurt instead of coconut milk, featuring chicken offal—liver, gizzard, and heart—each contributing distinct textures and concentrated flavors. Roasted spices like cinnamon, clove, and cardamom create warming aromatics, while fresh chilies provide signature heat. The dish documents how Bangkok’s noble kitchens adapted Islamic cooking techniques before democratization, preserving methods that would shape modern Thai cuisine.

Recipe

Article

August 2025

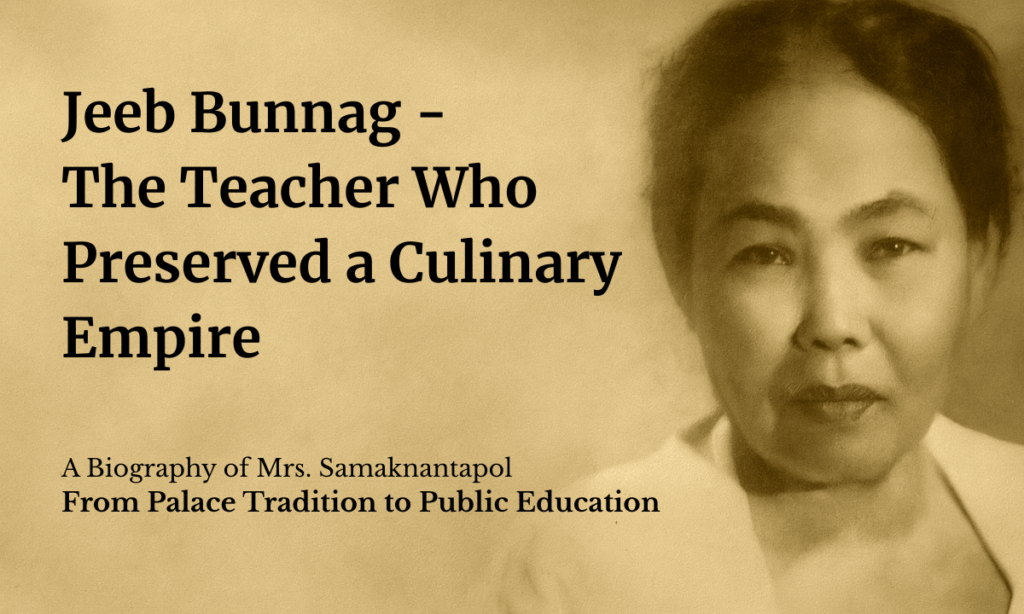

Jeeb Bunnag – The Teacher Who Preserved a Culinary Empire – A Biography of Mrs. Samaknantapol

The life of Mrs. Samaknantapol (Jeeb Bunnag) (นางสมรรคนันทพล (จีบ บุนนาค)) offers a direct view into the transmission of Thai culinary knowledge across a century of change. Her teaching, writing, and documentation preserved the structures of palace cuisine while shaping methods that could be studied and applied in classrooms throughout modern Bangkok.

Her 1933 work Samrub Raawp Bpee (สำรับรอบปี) remains an unparalleled record: 365 complete Samrub, old style Siamese meal sets, arranged with precision, reflecting daily rhythms of eating that were already disappearing from common practice. Through her work, we can study not only individual dishes but also the organization of meals and the cultural reasoning that guided them.

As someone who follows her teaching, I approach this story with both historical and practical attention. Her writing has informed my own study of Thai cuisine, and years of cooking from her instructions have shown me the clarity and discipline of her teaching. This account presents her life within its contexts—family, education, print culture, and the evolving society of twentieth-century Siam—while also acknowledging how her work continues to guide readers today.

Her 1933 work Samrub Raawp Bpee (สำรับรอบปี) remains an unparalleled record: 365 complete Samrub, old style Siamese meal sets, arranged with precision, reflecting daily rhythms of eating that were already disappearing from common practice. Through her work, we can study not only individual dishes but also the organization of meals and the cultural reasoning that guided them.

As someone who follows her teaching, I approach this story with both historical and practical attention. Her writing has informed my own study of Thai cuisine, and years of cooking from her instructions have shown me the clarity and discipline of her teaching. This account presents her life within its contexts—family, education, print culture, and the evolving society of twentieth-century Siam—while also acknowledging how her work continues to guide readers today.