Siamese Recipe Archive — Heritage Collection

Mom Ying Supha (หม่อมหญิงสุภา)

Pen name (นามแฝง) | 1949–1950 |

Royal-Style Thai Cuisine

Introduction

The author published under the pen name Mom Ying Supha (หม่อมหญิงสุภา), signing the preface of her book ‘Recipes for Preparing Yam Dishes’ (ตำราการปรุงอาหารยำ) as M.L. Ying Supha (ม.ล. หญิงสุภา)—a title indicating royal descent. No further biographical record has been located. On the cover of the book Pornthip’s Savory Dishes (กับข้าวพรทิพย์), however, she advertises that the recipes collected are all “Royal kitchen-tested” and were cooked, savored, and enjoyed by high-ranking members of the Royal family (เป็นตำรับจากห้องเจ้านายเสวยสบพระทัยมาแล้ว).

These books appeared in 1949 and 1950, during a period when recipes previously held within palace and aristocratic households began entering public circulation. Former palace residents published recipes commercially or through cremation memorial books. A literate middle class, eager for culinary refinement, created a market for such knowledge.

This dissemination continued a pattern established in Siamese aristocratic culture during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The effort to be viewed by Westerners as a “civilized nation”—and thus maintain sovereignty—drove administrative reforms, architecture, and dress codes. Early Siamese culinary works followed the format of popular Western cookery books, and this fashion of revealing culinary secrets to the general population, which began in the royal courts, continued into the period when Mom Ying Supha’s books appeared. The tradition gradually refined the gastronomic techniques of commoners and shaped Thai food into what it is today.

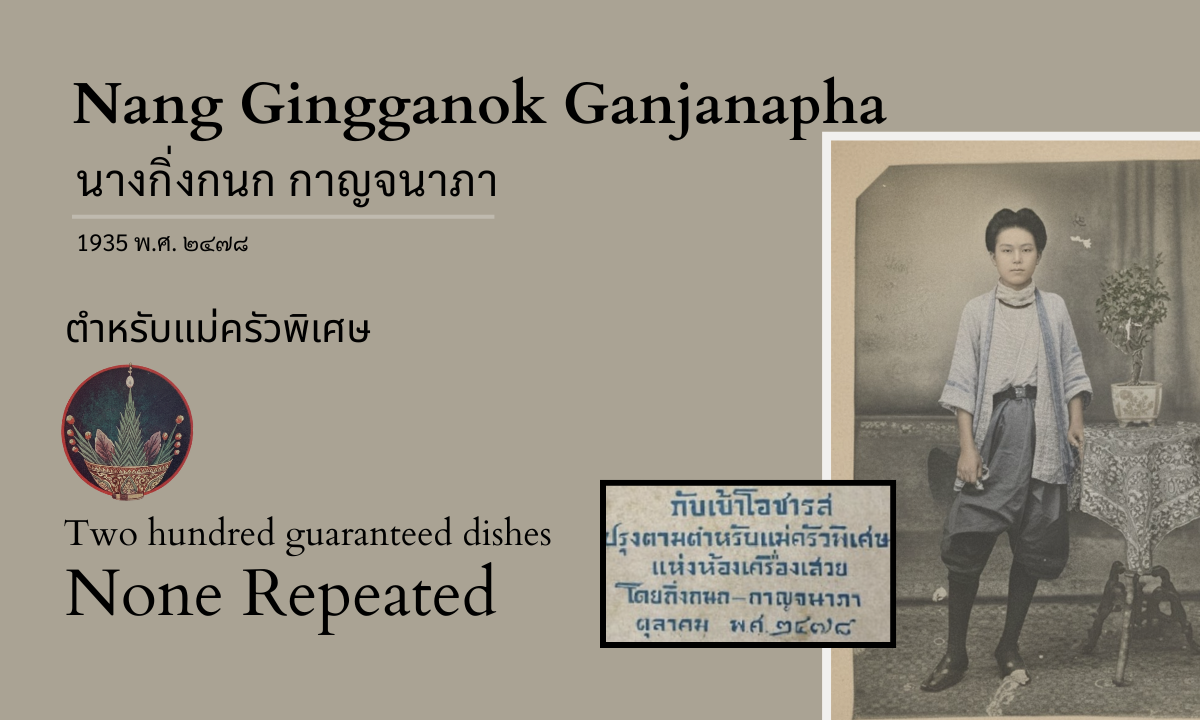

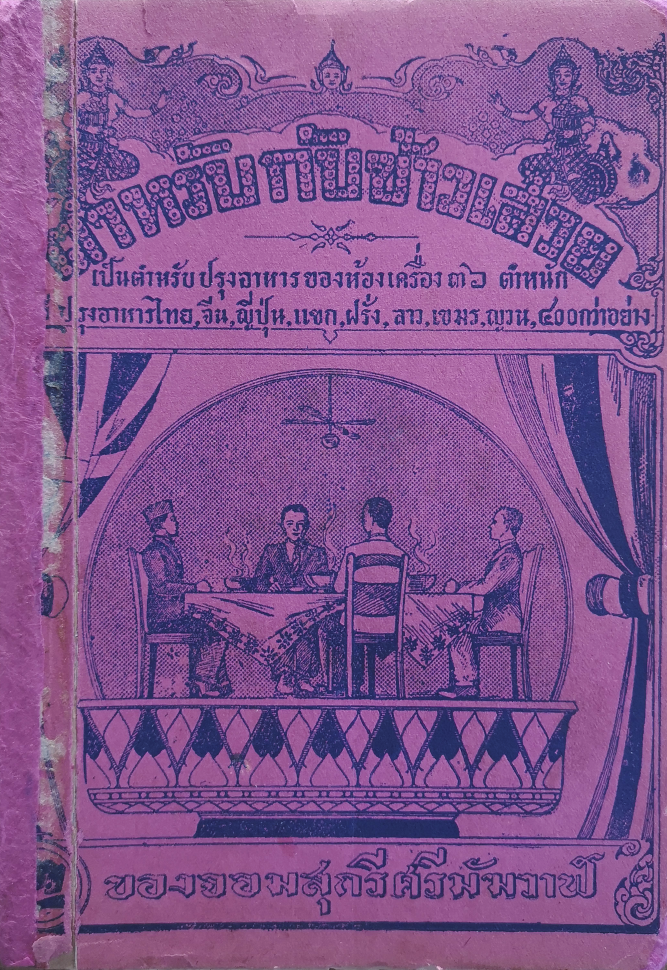

Mom Ying Supha fits a pattern of pseudonymous authors from this era. The most prominent parallel is Jomsukhri Srimakhawan (จอมสุกรี ศรีมัฆวาฬ), whose Recipes from 36 Kitchens (ตำหรับกับข้าวเสวย) was first published in 1939, with a second printing in 1941. That author, also writing under a pen name, had served in the royal court during the reigns of King Rama VI and VII, and compiled 541 recipes of Thai, Chinese, Japanese, Western, and Khaek cuisine from the royal kitchens. The constructed pen name—claiming palace authority while preserving anonymity—appears to have been a recognized convention of the period.

Mom Ying Supha on Cooking

In the preface to Pornthip’s Savory Dishes (กับข้าวพรทิพย์), addressed “To Those Who Are Interested” (แด่ท่านผู้สนใจ), Mom Ying Supha sets out her philosophy. While Thai cooking—like English, French, or American—often uses standardized measurements, household cooks do not maintain such standards. They rely on estimation (การคะเน), and this is sufficient. The cook develops expertise through tasting (ใช้ปากชิม), adjusting ingredients according to preference (ลดหย่อนเพิ่มเติมเครื่องปรุงนั้นตามชอบใจ), and building skill (ความชำนาญ) that produces food pleasing to those who eat it. Thai regional cooking, she writes, is inherited property (สมบัติสืบเนื่อง) and instinct (สัญชาติญาณ)—something that can be known without studying any cookbook. Yet she questions whether someone who has never cooked can produce food with good flavor. Even a dish using only two or three ingredients will fail if one element is missing or improperly combined.

Beyond ingredients, method (วิธีทำ) and roht meuu (รสมือ)—one’s delectable hands—are equally important. A cook who lacks sufficient technique will still produce food whose taste is off. Meat dishes, for instance, can turn unpleasantly gamey (เหม็นคาว). Some cooks possess skill and knowledge of all ingredients, yet lack what she calls “charm in the touch” (เสน่ห์ในรสมือ). Their cooking lacks deliciousness (ความเอร็ดอร่อย), lacks thoughtfulness (ความคิดอกคิดใจ), and fails to win appreciation from family and society. Thai cooking, she concludes, is neither too difficult nor too easy. Roht meuu (รสมือ) and expertise (ความชำนาญ) remain essential.

In the preface to Recipes for Preparing Yam Dishes (ตำราการปรุงอาหารยำ), she writes more personally: she created these recipes by cooking and eating them herself (ข้าพเจ้าได้พยายามสร้างโดยใช้ฝีมืออาหารปรุงทำรับประทานมาแล้ว). She asks readers to consider the appropriateness of ingredients (ความเหมาะเจาะแห่งเครื่องปรุง) to achieve food with good flavor—cooking with one’s delectable hands (roht meuu dee; รสมือดี).

The Books in This Collection

The Siamese Recipe Archive holds four works attributed to this author:

Recipes for Preparing Yam Dishes (ตำราการปรุงอาหารยำ), 1949 (พ.ศ. 2492). Thai salads and dressed dishes—preparations where raw and cooked ingredients meet acid, heat from chilies, and the cook’s judgment about balance.

Pornthip’s Savory Dishes (กับข้าวพรทิพย์), 1949 (พ.ศ. 2492). The main savory repertoire, organized by category: curries (ประเภทปรุงอาหารเผ็ด), side dishes (ประเภทปรุงอาหารเครื่องเคียง), and chili relishes (ประเภทปรุงเครื่องจิ้ม). “Pornthip” (พรทิพย์), meaning “divine blessing,” appears in three of the four titles in this collection.

Pornthip’s Sweets (ของหวานพรทิพย์), 1949 (พ.ศ. 2492). Thai confectionery and desserts, a category requiring precise technique and often associated with palace training, where sweets marked ceremonial occasions and demonstrated a cook’s refinement.

Combined Cookbook: Thai-Chinese-Western (รวมตำรากับข้าว ไทย-จีน-ฝรั่ง), 1950 (พ.ศ. 2493). Five volumes spanning three culinary traditions, reflecting Bangkok’s cosmopolitan character and the aristocratic kitchen’s incorporation of foreign techniques.

The books were published commercially through Chamroen Sueksa (จำเริญศึกษา) in Bangkok, not as cremation memorial volumes—a choice suggesting the author intended these recipes for wide circulation.

The Language of Palace Cooking

The table of contents of Pornthip’s Savory Dishes reveals a vocabulary shaped by court culture. Dishes carry names that are literary compositions: Egg of the Moon (เครื่องเคียงไข่ดวงเดือน), Three Kings (เครื่องเคียงสามกษัตริย์), The Wealthy Man’s Taro (เครื่องเคียงเศรษฐีสักตมัน), Pretending to Be Delicious (เครื่องจิ้มแสร้งว่าอร่อย). A fish curry becomes Fish of Steady Practice (แกงมัฉฉาอาจิณณ์). A sparrow dish becomes Sparrow of Varied Flavors (แกงนกกระจาบชรส).

This naming practice—where a dish’s title carries aesthetic and sometimes playful weight—distinguished palace cooking from common practice. The names required a cook who could read them, a household that would recognize the reference, and a tradition where food preparation carried cultural meaning beyond nutrition. Mom Ying Supha preserved this vocabulary alongside the recipes themselves.

The identity behind Mom Ying Supha (หม่อมหญิงสุภา) may remain unknown. The recipes do not. What follows is the work of a cook who claimed palace knowledge, published under a name constructed to carry that authority, and left behind four books that have survived more than seventy years to reach this archive.

About the Siamese Recipe Archive

The Archive collects and translates historical Thai culinary manuscripts—primary sources written by the cooks, noblewomen, and food professionals who shaped the cuisine of the Rattanakosin era. Each document records practical knowledge shaped by its moment: what was available, what the tradition demanded, what a specific cook decided under real constraints.

Visit Heritage