Siamese Recipe Archive — Heritage Collection

None Repeated

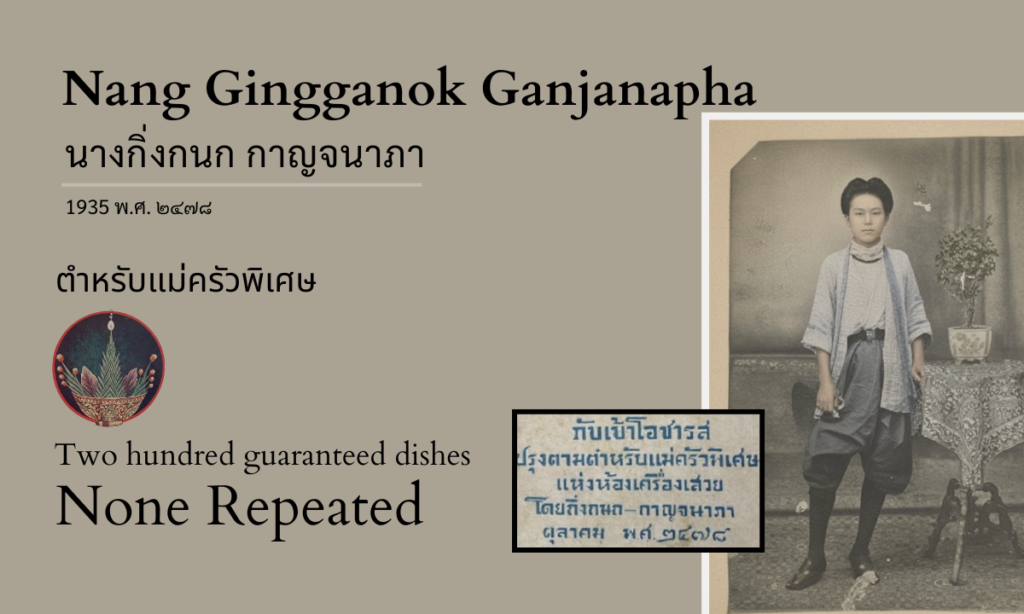

Nang Gingganok Gaanjanaaphaa (กิ่งกนก กาญจนาภา)

1935 (พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘) | Royal Thai Cuisine

A Market Complaint

The title uses an archaic spelling—”เข้า” rather than the modern “ข้าว” for rice. “กับเข้า” means accompaniments for rice, the preparations that transform plain rice into a meal. “โอชารส” (o:h chaa rot) is used to express delight in the delectable flavor of a dish. It goes beyond a simple statement of the food being good; it is a celebration of its exquisite taste.

Gingganok Gaanjanaaphaa (กิ่งกนก กาญจนาภา) opens her 1935 (พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘) cookbook with a complaint:

Even though the market is already overflowing with cookbooks, most are small books in the eight-section format, containing no more than a hundred dishes. This book copies that book, that book copies this one, back and forth—only the names change. Even if you buy two or three books, you only get the recipes of one. The buyer does not receive benefit according to their true wishes.

(แม้ในท้องตลาดจะมีตำรากับข้าวขายกันอยู่แล้วเกลื่อนกล่นก็จริง แต่โดยมากเป็นหนังสือขนาดเล็กถึงแปดแยก บรรจุกับข้าวไม่เกินร้อยอย่าง ทั้งเล่มโน้นซ้ำเล่มนี้ เล่มนี้ซ้ำเล่มนั้นอยู่ไปมา เปลี่ยนแต่ชื่อ แม้จะซื้อสักสองสามเล่ม ก็ได้รายชื่อกับข้าวแต่จำนวนเล่มเดียวนั่นเอง ซึ่งผู้ซื้อย่อมไม่ได้ประโยชน์สมความปรารถนาอันแท้จริง)

Her solution was consolidation. She gathered recipes from the special cooks of the royal kitchen (แม่ครัวพิเศษแห่งห้องเครื่องเสวย)—women with established reputations in palace culinary service—and assembled them into a single comprehensive volume: over two hundred preparations, none repeated.

I have compiled recipes from famous royal kitchen staff into this volume, containing over two hundred dishes, and I guarantee none are duplicated. You buy this one book, and it may serve you better than all the others.

ข้าพเจ้าจึงได้รวบรวมกับข้าวจากตำหรับของแม่ครัวที่มีชื่อเสียง สามารถบรรจุกับข้าวได้สองร้อยกว่าอย่าง และรับรองว่าไม่ซ้ำกันในตัวเลย ท่านซื้อตำราเพียงเล่มเดียว อาจคุ้มตำราเล่มอื่นๆ เสียได้เป็นอย่างดี)

Three Women

The book’s postscript names three women who contributed to the compilation: Khun Praphai (คุณประไพ), Khun Jira (คุณจิรา), and Khun Noi (คุณน้อย). Gingganok thanks them for their substantial help and acknowledges that some recipes came from these collaborators—preparations “beyond her own ability to find.” The cookbook is therefore a collaborative document, drawing on multiple sources of knowledge. Who these three women were, and what their relationship to royal kitchen practice may have been, the text does not specify.

Hua Hin, July 1935 (กรกฎาคม พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘)

Gingganok wrote from a seaside house in Hua Hin (หัวหิน), completing the manuscript on July 24, 1935 (๒๔ กรกฎาคม พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘). The book appeared in print that October (ตุลาคม พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘), published by Akson Charoen That Printing House (โรงพิมพ์อักษรเจริญทัศน์), also known as Heng Hua Hong (เฮงฮั่วฮง), near Choeng Saphan Lao Ching Cha (เชิงสะพานเล่าชิงช้า) in Phra Nakhon (พระนคร), priced at three baht (๓ บาท). The owner listed on the publication page is Nai Lek Techawikay (นายเล็ก เตชวิกัย)—likely the publisher or financial backer rather than the author.

The Hua Hin (หัวหิน) detail is worth noting. By 1935 (พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๘), Hua Hin had been a royal retreat for decades, a place where Bangkok’s elite built seaside homes. That Gingganok wrote there, and mentions it specifically, suggests her social position—someone with the leisure and means for extended stays at a fashionable resort town. She acknowledges writing “during a time of rest,” yet maintains the work will serve housewives according to their circumstances.

Palace to Kitchen

The book closes with a section Gingganok describes as particularly suited to the housewife (แม่เรือน)—the woman who manages a household. These are composed menus, dishes organized into complementary sets. This pedagogical choice suggests an intended audience: women responsible for daily meal planning who needed guidance on what preparations work together.

The bulk of the collection, however, draws from professional palace cooking. The tension between these two orientations—high court cuisine and domestic application—runs through the project. Gingganok gathered recipes from trained specialists and presented them for household use.

Silences

No biographical record of Gingganok Gaanjanaaphaa (กิ่งกนก กาญจนาภา) beyond this text has been located. The specific royal kitchen staff whose recipes appear in the collection are not named. The three collaborators receive thanks but no further identification. The book presents itself as a transmission from palace practice to domestic kitchen, but the chain of transmission—who taught whom, which recipes came from which source—remains undocumented.

Two Hundred Preparations

What survives is the collection itself: over two hundred preparations representing what Gingganok and her collaborators understood as royal kitchen cooking in the mid-1930s (พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๐). The recipes document technique, proportion, and method as these women knew them. Whatever biographical questions remain open, the cooking knowledge is present on the page.

About This Edition

Thaifoodmaster presents Exquisite Accompaniments for Rice (กับเข้าโอชารส) with original Thai text and English translation. Recipe measurements have been converted for contemporary use while preserving the proportional relationships Gingganok recorded. The set menu section, which Gingganok considered essential for household application, appears as she organized it.

The Recipe Archive

About the Siamese Recipe Archive

The Heritage project preserves pre-1950s Thai culinary manuscripts—translating, contextualizing, and making accessible the recorded knowledge of Siamese cooks before it disappears entirely.

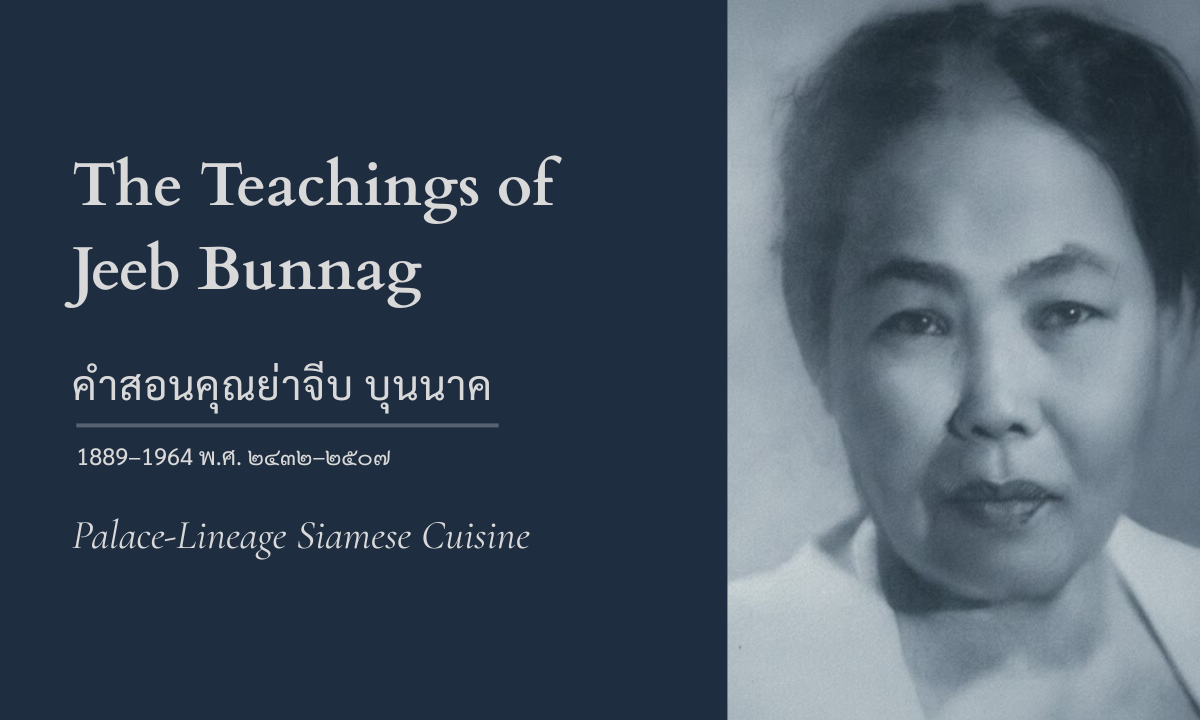

The project is led by Hanuman Aspler, founder of Thaifoodmaster, who has spent over three decades studying ancient Siamese manuscripts and developing a methodology for understanding Thai cuisine as a language with its own grammar and syntax. The archive provides primary sources for learning this culinary language—not recipes to follow, but grammar to internalize.