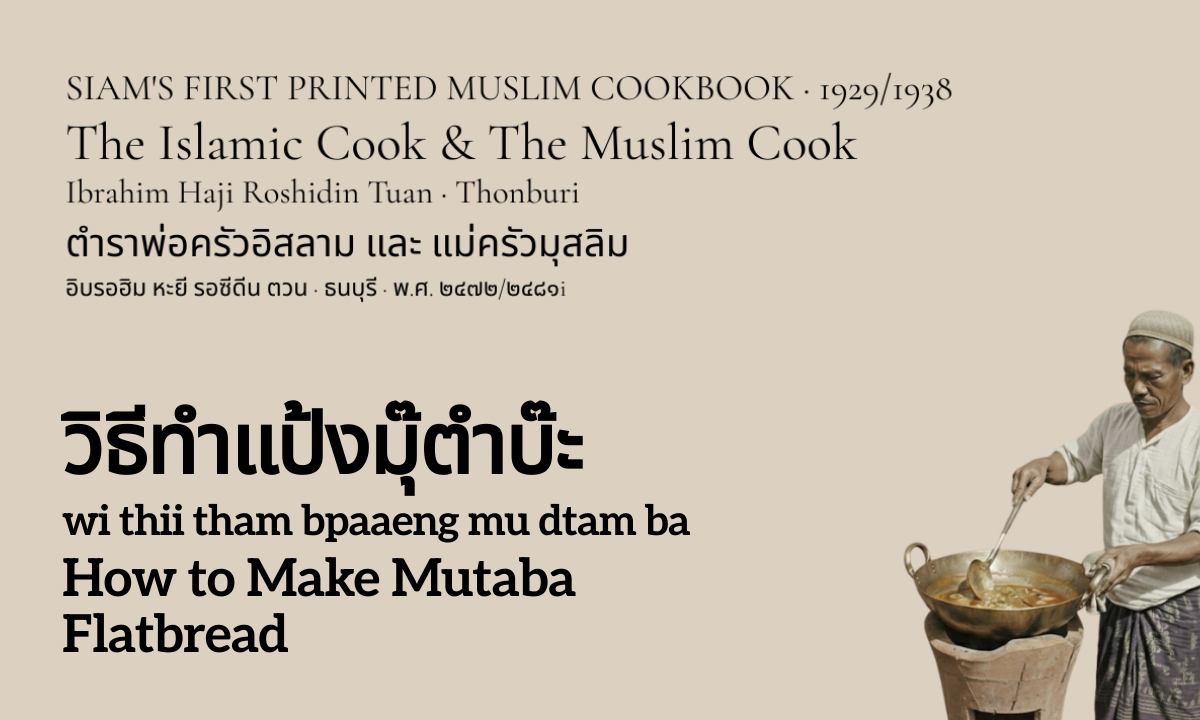

SIAM’S FIRST PRINTED MUSLIM COOKBOOK. 1929/1938

The Islamic Cook & The Muslim Cook

Ibrahim Haji Roshidin Tuan Thonburi

ตำราพ่อครัวอิสลาม และ แม่ครัวมุสลิม

อิบรอฮิม หะยี รอซีดีน ตวน – ธนบุรี พ.ศ. ២៤៧២/២៤៨១

In brief

In September 1929 (กันยายน พ.ศ. 2472), a Thonburi (ธนบุรี) Muslim cook, Hibrohem Haji Rosidibintuan (ฮิบรอเฮม หะยี รอซิดีบินตวน), published Tamra Phokhrua Islam (ตำราพ่อครัวอิสลาม)—likely Thailand’s first fully “khaaek” (แขก) / Islamic-focused Thai-language cookbook—because khaaek food was popular but Thai recipe guides were scarce. He positioned the book as practical and socially useful (helping readers cook for themselves, get kitchen work, broaden skills, and even help married women vary meals), while also promoting his bottled curry spice mix (เครื่องกะหรี่). The book compiled 51 savory dishes plus desserts, a drink like Nam Sarabat (น้ำซาระบัด), and even pickling methods—reflecting how influential Muslim culture and cuisine were in Siam at the time, though little else is known about the author.

Introduction

A professional caterer’s working manual from the Thai-Muslim community of Thonburi (ธนบุรี), documenting the cooking methods of a practicing Muslim cook who made his living preparing food for hire.

The 1938 The Muslim Cook (แม่ครัวมุสลิม) appears to be a later edition of recipes Ibrahim (อิบรอฮิม) first published in 1929 as The Islamic Cook (พ่อครัวอิสลาม), a pamphlet that accompanied his commercial curry powder (ผงกะหรี่) blend. The recipes in both texts overlap substantially, dating the core material to 1929. Ibrahim (อิบรอฮิม) himself claimed no Thai-language cookbook for Muslim cuisine existed at the time of publication—making this the earliest documented Thai-Muslim recipe collection.

The manuscript contains 40 recipes divided between savory dishes (อาหารคาว) and sweets (หวาน). The savory section covers the full range of Thai-Muslim cuisine: korma (แกงกุร๊ะหม่า), gudee (แกงกุดี), mussaman (แกงบุสหมั่น), biryani (ข้าวบุร๊ะยานี), khao mok gai (ข้าวหมกไก่), satay sauce (น้ำพริกสะเต๊ะ), and several curry variations including dunyanee (แกงดุนยานี) and daraja (แกงดาราจา). The sweets include murtabak (มุ๊ตำบ๊ะ) in three styles—savory (เค็ม), sweet (หวาน), and Turkish (เตอรกี)—plus roti (โรตี), ghee-flour pudding (แป้งกัสรุยี), butter custard (ขนมหม้อแกงเนย), and rose-shaped fried pastry (ขนมดอกกุหลาบ).

What makes the text distinct is its source. Ibrahim (อิบรอฮิม) wasn’t documenting palace cuisine or household cooking—he was recording the techniques of a professional caterer working weddings, funerals, and hired events in 1930s Thonburi (ธนบุรี). His recipes specify quantities for feeding crowds: half a dozen chickens, thirteen kilos of meat, seven coconuts. The book may also function as promotional material for his catering services and curry powder business—a possibility worth considering given the commercial context of its origins.

The manuscript preserves specific techniques now rarely documented: sealing pot lids with wheat flour paste (แป้งสาลี) for dum cooking, smoking dishes with freshly burned coconut shell (กะลา), the exact ratio of ghee (น้ำมันเนย) to coconut oil (น้ำมันมะพร้าว) for gudee (แกงกุดี). His stuffed chicken recipe calls for piercing the bird with a metal skewer (เหล็กแหลม) to ensure even cooking—practical knowledge from someone who couldn’t afford failures.

Ibrahim (อิบรอฮิม) sold his pre-mixed curry powder (เครื่องกะหรี่) by mail order from Si Yaek Ban khaaek (สี่แยกบ้านแขก), behind Wat Phichai Yat (วัดพิชัยญาติ). In his preface (คำนำ), he described the product’s advantages:

I’ve blended curry powder and packaged it nicely for your convenience, so you can use it right away without wasting time preparing and pounding it. It’s useful to take along on extended excursions to isolated locations where some of the various ingredients may not be available, and therefore the lovely fragrance of your cooking might be lost. It will keep up to a year if from time to time you put the bottle in the sun.

His preface (คำนำ) also explained his reasons for publishing: no Thai-language cookbook for Muslim cuisine existed. He positioned the book for three audiences—people who want to cook at home, professional cooks expanding their repertoire, and married women who might “change the flavor of food for their husbands” to prevent boredom.